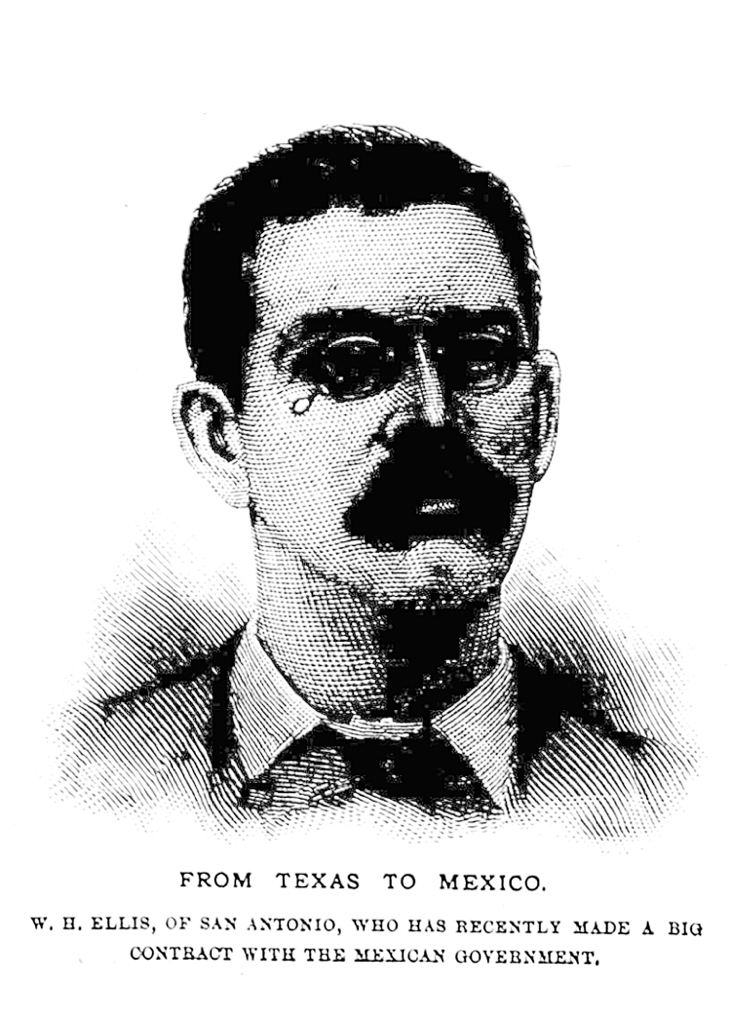

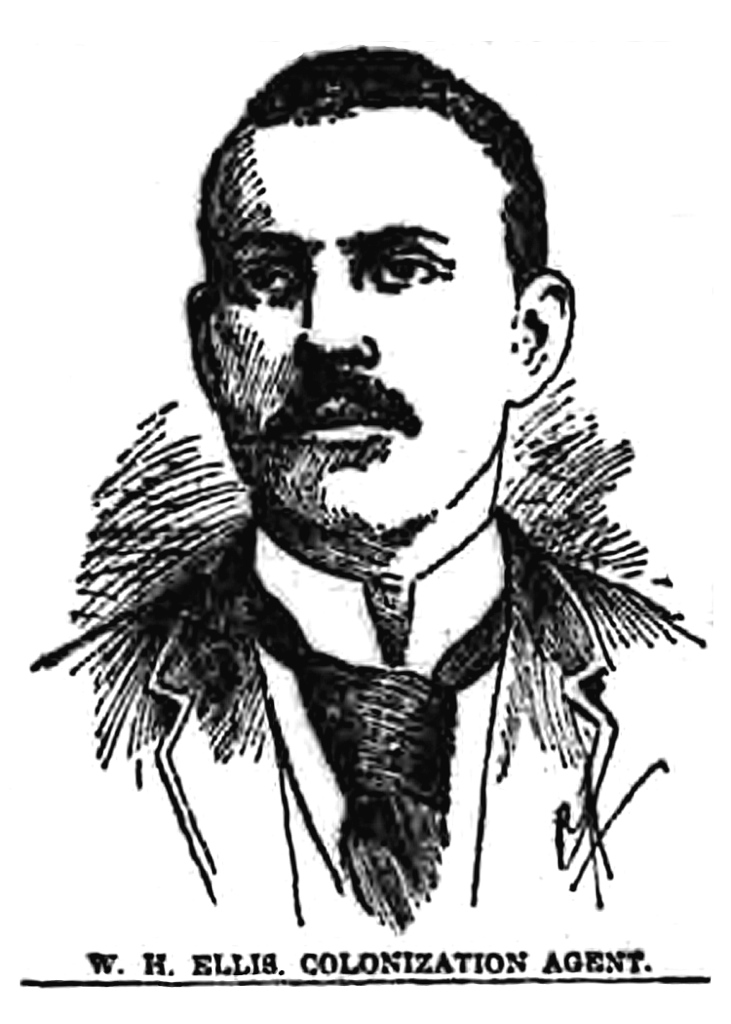

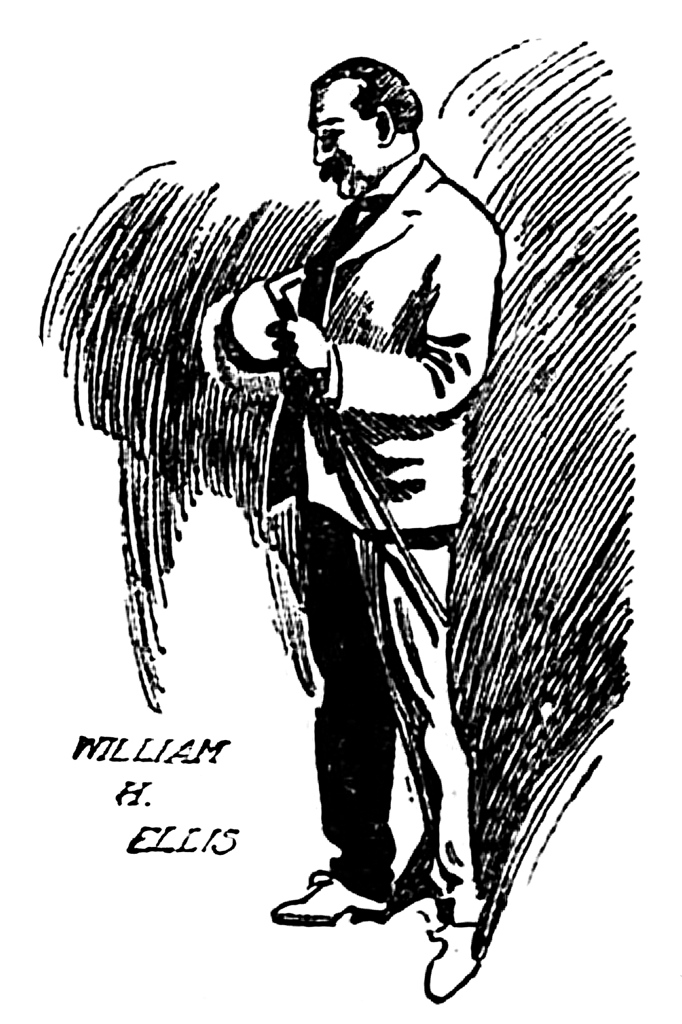

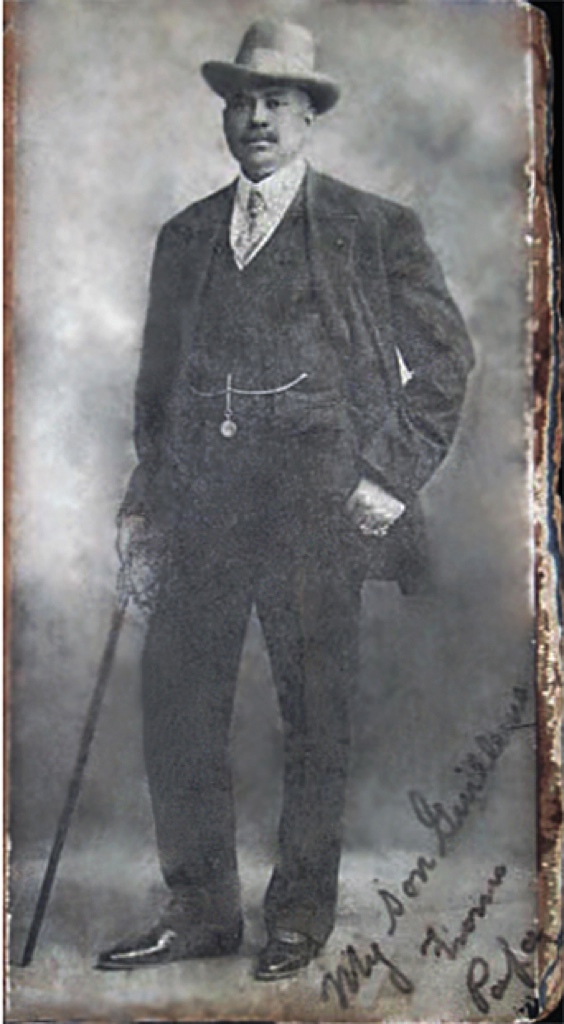

Images: Passing and the Racial Gaze

The Gilded Age was the golden age of racial passing. The rise of segregation in the aftermath of Reconstruction encouraged those Blacks with ambivalent features to present themselves as the members of another race. The increased mobility facilitated by the novel technology of the railroad made it easier than ever before to travel to a new town, where no one knew anything about your background and to adopt a new persona. And the sparseness of record keeping—few people at the turn of the century possessed passports, birth certificates, or other forms of official documentation—ensured that there existed no paper trail that could betray your “real” racial identity. So long as one could perform their new identity convincingly, they could “pass” as a member of a different racial group.

Although commonly perceived as a question of physical appearance, in which the visual marker of skin color was the preeminent issue, passing, as the history of William Ellis reveals, in fact involved multiple factors. How one wore one’s hair, for instance, could change perceptions of one’s racial category as could the way that one dressed or the language that one used. Thus, when the teenaged Langston Hughes wanted to buy a train ticket for a whites-only first class coach in Texas, he pomaded his hair “in the Mexican fashion” and spoke to the clerk in Spanish. James Weldon Johnson likewise managed to finesse a place in a whites-only compartment by resorting to Spanish and by wearing a distinctive Panama straw hat of the sort favored by many Latinos.

William Ellis used similar strategies in his effort to reinvent himself. He spoke fluent Spanish from his time growing up in Victoria, where he had picked cotton alongside Mexican field hands. He dressed exquisitely (as one newspaper put it, he wore a “long brown overcoat of costly texture, . . . thick white silk handkerchief around his neck . . . fingers sparkl[ing] with many valuable diamonds”). He cultivated an elegant mustache of the sort favored by upper-class Mexicans. He selected to live and work in places like Central Park West and Wall Street that were well outside the neighborhoods where most African Americans resided.

These images, culled from a variety of newspapers and personal collections, capture the multiple ways in which William Ellis (and his alteregos of Guillermo Ellis and Guillermo Eliseo) was perceived during his lifetime.